It was my turn this Shabbat to deliver a d’var Torah (commentary) after the group discussion in Temple Sinai’s weekly Torah study class. This week’s portion, Vayetzei, covers Genesis 28:10 to 32:3, but the class discussion focused only on the final third. So I chose to center my presentation on an earlier section, the rivalry between Rachel and Leah. Here it is.

Like many of the parshot in Genesis, a lot happens during Vayetzei. Jacob sets out from his family’s home in Beersheva, both to flee the anger of Esau and to find a wife from among his mother Rebecca’s family. Lying down to sleep on a rock, he dreams of a ladder or ramp to heaven with angels going up and down. In his dream, God stands beside him and blesses him, saying his descendants shall spread out to the four corners of the earth and all the families of the earth will be blessed by them.

Jacob wakes and names the site Beth-el, House of God, which is located about ten miles north of Jerusalem, near what today is the Palestinian city of Ramallah on the West Bank.

Jacob continues on to Haran, which is quite a long journey, up through Syria into what is today Turkey. He meets his cousin Rachel at a well, much as Abraham’s servant found Isaac’s future wife Rebecca at a well. Rachel’s father Laban agrees to let him marry Rachel if he works unpaid for seven years; then on the wedding night, Laban tricks him by substituting Rachel’s older sister Leah—a parallel with how Jacob tricked his own father by pretending to be Esau. Laban requires Jacob to work without pay for another seven years in order to marry Rachel too.

The Torah then enters into an extended section on the two sisters’ childbearing—or lack of childbearing. Eventually Jacob decides to return home, and there is an episode of one trickster tricking another trickster, with Jacob slyly arranging to get possession of many of Laban’s sheep and goats. That gets us up to the portion of Vayetzei that we read together today in class.

But I’m going to return to that long section about childbearing and the relationship between Leah and Rachel.

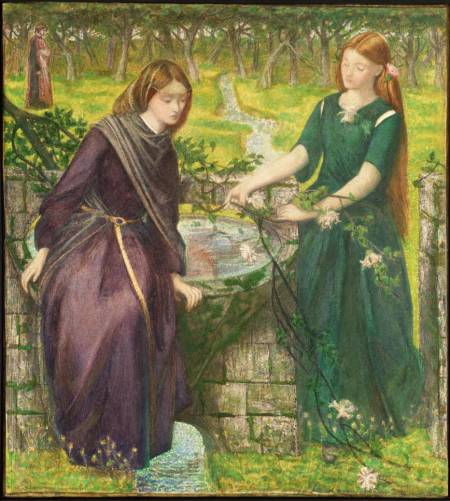

Rachel and Leah, as imagined by 19th century English poet and painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti. (It looks a little more like a romanticized Renaissance England than the ancient Middle East, don’t you think?)

The Torah tells us that Jacob loved Rachel more than Leah. “And God saw that Leah was unloved and he opened her womb, but Rachel was barren.” Leah conceives and bears one son—Reuben—then another, and another, and another— four sons in a row while Rachel can’t get pregnant.

Both of these sisters are in deep emotional pain.

Infertility is certainly traumatic, especially in a society like the ancient middle east where women were valued only as mothers of sons. “Give me children, or I shall die,” Rachel pleads to Jacob in a dramatic statement of how crucial childbearing was to her.

But I felt an even deeper identification with Leah. She was married, presumably without any say in the matter, to a man who didn’t love her. When her first son is born she chooses the name Reuben, saying “It means the Lord has seen my affliction. It also means, ‘ Now my husband will love me.” But it doesn’t help. Whenher second son comes, shge says, “The Lord heard that I was unloved and has given me this one also.” And it doesn’t help. And then the third. She says, “This time my husband will become attached to me for I have borne him three sons.” And it still didn’t help.

She is doing everything in her power to win Jacob’s love —everything possible to fulfill the role expected of her, to provide healthy male heirs, everything that anyone in her world would ask of her—and it still doesn’t help.

I imagine this desperate young woman, getting her hopes up over and over—this time it will work! this time it really will!—and each time it doesn’t. Haven’t we all been there at some time, trying so hard and yet knocked down over and over again?

Perhaps when we were in our teens, infatuated with some boy or girl, convinced that If I wear my new red miniskirt, they’ll notice me! If I bake chocolate chip cookies, they’ll notice me! If I help them with their math homework, they’ll notice me! Trying over and over, so sincerely, and of course they don’t notice.

Or perhaps at work, trying to get a promotion: If I stay until 6 pm each night, they’ll notice me! If I turn in the most thorough report ever, they’ll notice me! If I learn to play golf, they’ll notice me! Trying over and over, playing by all the rules, and of course they don’t notice. Because you’re female, or Black, or you’ll never be one of the “old boys,” or whatever….

In those modern scenarios, the advice is clear: Leave. Find a new crush, find a new job. But Leah, as a wife in the ancient Middle East, had no option of leaving. And the stakes for her were so much higher than a junior-high crush or a promotion. This was pregnancy and childbirth—nine months of pregnancy, hours or days of labor, things that in those days truly risked death. But none of it made Jacob love her.

So the competition went on, dragging in other parties like a world war. After Leah’s fourth son, Rachel still can’t conceive and so gives her servant—her handmaid— Bilhah to Jacob as a concubine.

(Just an aside: The Torah has Rachel saying to Jacob, “Here is my maid Bilhah. Consort with her, that she may bear on my knees and that through her I too may have children.” Some commenters including Robert Alter say that “bearing on my knees” refers to an ancient practice of placing children on someone’s knees as a ritual of adoption. But writer Margaret Atwood chose to take this literally in her patriarchal dystopia of The Handmaid’s Tale—this is the source for the horrible practice of the handmaid literally giving birth between the knees of the patriarch’s wife.)

But back to Rachel and Leah and their childbearing competition. Leah is ahead, 4 to nothing. But then Rachel’s servant Bilhah bears two sons by Jacob, and Rachel says “A fateful contest I waged with my sister, and I have prevailed.” You can imagine her doing an ancient Mesopatamian fist punch in the air.

So Leah then gives Jacob her servant Zilpah, who bears two sons. This is starting to sound like the US-Soviet arms race. It parallels the sibling rivalry between Jacob and Esau, yet in some ways it is more intense and painful because both siblings were so aware of it—two women living side by side in the same family compound for 20 years, with close-up, unavoidable views of each other’s ongoing victories and failings.

It’s horrible to think of these two sisters in a permanent state of war. Some of the commentators seemed to think so too: There are midrashim that weave stories of empathy and solidarity between Leah and Rachel.

One midrash from the Talmud says that Rachel knew in advance of Laban’s wedding-night trick, warned Jacob, and he came up with a way to defeat Laban’s scheme.

Jacob gave Rachel signs [so that he would be able to recognize her on their wedding night].

When Leah was brought under the wedding canopy, Rachel thought: “Now my sister will be shamed [when Jacob discovers the fraud and does not marry her].” She gave the signs to Leah. (BT Bava Batra 123a).

According to the Rabbis, Laban would not have succeeded in deceiving Jacob without Rachel’s involvement. Rachel had to choose between her love for Jacob and her compassion for her sister, and she decided in favor of the latter. The most extreme description of Rachel’s act of self-sacrifice appears in Lam. Rabbah, according to which Rachel entered under Jacob and Leah’s bed on their wedding night. When Jacob spoke with Leah, Rachel would answer him, so that he would not identify Leah’s voice (Lam. Rabbah [ed. Vilna] petihtah 24).

I would like to think that, alongside the pain of infertility or being the second-choice wife, there was also empathy and solidarity between the sisters. Like the rest of the Torah, this parshah was written by men, from stories handed down by men, and this reproductive arms race may be their outsider’s view of what was going on within the family tent while the men were away with the flocks.

Let’s look at what happens next, after Bilhah and Zilpah have each birthed two sons and the total son count is up to eight. Reuben, Leah’s oldest son, brings her some mandrakes that he finds in the field. (Mandrakes, having a root that is bizarrely shaped like a human figure, have been imagined in many cultures to bring fertility.)

Mandrake root / Photo by Jenny Laird

Rachel asks Leah for some of the mandrakes, hoping to cure her infertility. Leah at first refuses, saying, “Was it not enough for you to take away my husband, that you would also take my son’s mandrakes?” But then Rachel promises that Leah can sleep with Jacob that evening in exchange for the mandrakes, and Leah agrees.

Leah goes out to meet Jacob that evening and tells him. “You are to sleep with me, for I have hired you with my son’s mandrakes.”

This is a truly shocking moment. Leah is in command for once—unlike her own wedding night, she has the power here. She is commanding Jacob to sleep with her. And not just commanding him, she is saying that she hired him, like you would hire a prostitute, like you would hire an ox to plow a field.

Perhaps her grief all those years was not just at being unloved—it was at being powerless, manipulated by her father in order to get more work out of Jacob, unable to choose her own fate. Here for once she is able to take fate into her own hands and turn the tables. Jacob in effect becomes a sex object here.

It’s not pretty, but perhaps it was satisfying or even restorative for Leah. Perhaps Rachel wanted to give her this gift of momentary power.

We don’t know. What we do know is that, three sons later, when Jacob is ready to leave Haran, the two sisters respond in unison.

“Then Rachel and Leah answered him, saying, ‘Have we still a share in the inheritance of our father’s house? Surely he regards us as outsiders, now that he has sold us and has used up our purchase price. Truly, all the wealth that God has taken away fronm our father belongs to us and to our children. Now then, do just what God as told you.”

In current slang, we might say there’s no daylight between the two sisters here. No rivalry, no disagreement. They have long been done with their father’s manipulation and are ready to leave—together—for Jacob’s promised land.

Smoke and (our own private) mirrors

March 19, 2022Today I delivered a drash (commentary) on the weekly Torah portion, which was Tzav (Leviticus 6:1 through 8:36). I won’t reprint the entire thing here, just the part I liked the most. :-)

Tzav primarily focuses on the role of the priests in carrying out sacrifices on behalf of the Israelites. Moses instructs Aaron and his sons on where to make the sacrifices, what to wear, how to dispose of the ashes, etc.

I was struck by the repeated use of language about “turning sacrifices into smoke.” This is the phrasing the writers of Tzav use to say that an offering should be completely burned up. For instance:

“The token portion of the meal offering shall be turned into smoke on the altar as a pleasing odor to the Lord.”

“The priest shall turn the (fat of the guilt offering) into smoke on the altar as an offering by fire to the Lord.”

“Moses washed the entrails and the legs with water and turned all of the ram into smoke.”

And so on.

Now, there are so many ways one could describe what is being done with these offerings. You could simply say that Moses burned up the entire ram. Or that Moses incinerated the ram. That he turned it into ash, that he turned it into cinders, that he burned it so thoroughly that the amount left was smaller than a pebble.

But over and over, Leviticus tells us that these offerings were “turned into smoke.”

Why this emphasis on smoke?

Thinking historically, perhaps this was another of many steps in differentiating Judaism from the surrounding religions. Many ancient religions saw gods as similar to humans in that they needed to eat, and these societies viewed sacrifices as literally feeding the gods. Judaism took a different view of God—as being above and beyond human needs such as eating— and wanted to make clear that these ritual sacrifices were not Doordash for God. The sacrifices were not food for God’s survival. Instead, they were something intangible to please and connect with God: a “pleasing odor to the Lord.”

But I also like to think about it metaphorically, especially as it applies to the guilt and sin offerings. The fiery sacrifice turns something solid and heavy and bloody into something light and airy and (to God, at least) pleasant smelling.

Isn’t that what we’d like to have happen with our transgressions and regrets? They weigh us down, we carry them heavily… but wouldn’t it be nice if we could let them float away into the air? Through the ritual of the sacrifice, that’s what these ancient Israelites were doing.

So, with your indulgence, let’s do a little thought experiment.

Close your eyes. Think of one thing you’ve done in the past week that you regret because it was wrong. It doesn’t have to be a big thing: In fact, it’s most likely a small thing. Were you rude to the clerk at Safeway? Did you snap at your spouse? Did you read a news story and respond with cynicism rather than open-hearted empathy? Did you share a piece of gossip that, inside, you knew you probably shouldn’t? Did you gloat over someone else’s troubles?

Take a minute. Think of one small thing that you regret. We’re going to sit here quietly while you come up with that thing.

(wait)

Okay, now picture that small thing as a heavy block of wood. It’s hard to lift. You’ve been lugging it around all week. You don’t want it, but there it is. It’s heavy.

And now — keep those eyes closed! — envision setting that block of wood on fire. You know what you did was wrong and you’ll think twice the next time such a situation comes up. You’ll do better. The block of wood is burning and getting smaller and smaller and lighter and lighter and this thing you regret is turning into smoke. There! It’s past. It’s floating away. You’ve learned something and will do better next time. The wood is gone and the weight is gone and the smoke is dissolving into a broad blue sky.

Take a deep breath now, a full breath. You’ll do better. You’re learning, all the time. It’s never too late to learn. Your lungs fill with fresh, clean air and the smoke is no longer even visible, but God smells the smoke from your offering and, indeed, it is a pleasing odor to Adonai.

Open your eyes.

Shabbat Shalom.

Tags: Dvar Torah, Leviticus, Priestly sacrifices, Sacrifices, Teshuvah, Torah commentary, Tzav

Posted in Judaism | 1 Comment »